Two Canadian Winter Olympic Sport Pioneers

By Fred Kallin

The first Winter Olympics were held in Chamonix, France, at the base of Mont Blanc in 1924. 2022 is very close to the 100th Anniversary of the those first Winter games. In this article we will recognize a couple of the early Canadian pioneers in the winter sports. Neither of these gentlemen were Olympic competitors and neither got wealthy from their efforts and yet their influence on Canadian Winter sports and on the Olympics was great indeed. The oldest of the Olympic winter sports, cross-country skiing, first appeared as a means of winter travel over 6,000 years ago. By the mid 19th century skiing started to become a leisure activity and competitive sport in Scandinavia. Cross-country skiing and ski jumping were the two original ski sports at the 1924 Olympics. As skiing became more popular, many people started to gravitate more and more to the hills because of the thrill and challenge of moving swiftly down the slopes. The Alpine sport events of slalom skiing and downhill skiing made their debut at the 1936 winter Olympics in Germany. As is true for many sports, skiing has evolved greatly over the years. Up until the 1930s, there wasn’t much of a distinction between downhill and cross-country skis. In Canada, there were no ski lifts until the 1930s, so people used the same skis to go up the hills and back down again.

By 1940 the Toronto ski club was the largest community ski club in the world, with over 7,000 member skiers. This rich skiing heritage is something we should recognize and celebrate in this Winter Olympics year.

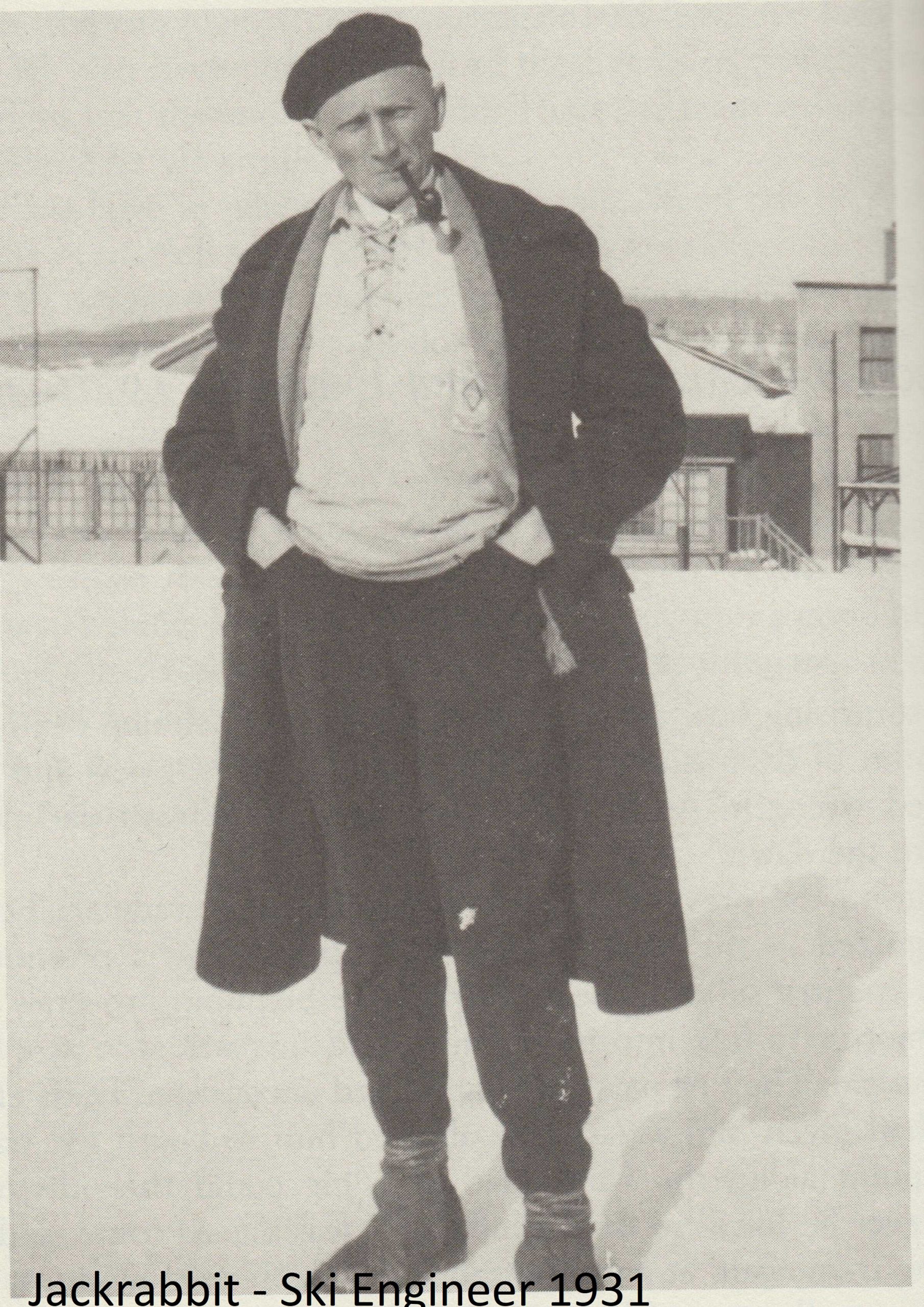

Herman (Jackrabbit) Johannsen

Herman Johannsen was born in the town of Horten, Norway on June 15, 1875. As is the custom in the Scandinavian countries, he learned to ski at the early age of 2½ years old. In 1883, Herman’s family moved to Christiania (Oslo). Herman and his friends would often go skiing together in the forests and hills above the city. At first, Herman’s father would come with the boys but after a while the boys started to go out on their own. The boys carried their own rucksacks with food and extra clothes for longer excursions. They went further and further from the city on each outing and eventually started making trips into Nordmarka ( a wild plateau about 250 metres high and about 1,000 square kilometres to the North of Oslo). The boys banded together and established their own headquarters at Slagtern, a small farmhouse up in Nordmarka. Here they could get meals and sleep overnight for a small fee. The Slagtern family would keep an eye on the boys, who livened things up for the family. The boys eventually rented a little one room cabin on the property and that became their clubhouse. They would continue coming to Slagtern through all of their teen years, and also started to learn some other new popular ski sports such as Ski Jumping and Downhill Skiing.

Herman Johannsen went on to earn a degree in Mechanical Engineering and came to Cleveland in 1901 to work in an engineering office for a manufacturer called Brown Hoist. He also met his future wife Alice Robinson in Cleveland one day while he was out skiing after a snow storm. Alice had been skating on a pond when Herman came down a hill and on to the ice. Alice and her friends were intrigued, as none had ever seen skis before.

By 1903 Herman was traveling around the US and Canada doing customer visits and sales. On one trip up to North Bay, he went out with the surveyors to inspect the route for the Northern Ontario Railway. This gave him better insight to recommend the proper equipment for the conditions. He also made his first contact with the Cree, through whose territory the railway was being constructed. Herman visited one of their encampments that winter and brought his cross-country skis. He skied with the men as they went out to follow their trap lines on snowshoes. The Cree were astonished at how rapidly Herman could move through the bush on his skis. They said he moved through the woods like a jackrabbit. Herman also learned some of the Cree language. He had great respect for the Cree, and always looked forward to meeting them again.

Herman and Alice were married in 1905, and Herman continued to work as a consultant selling construction equipment and hoists for several companies. Alice went with Herman on an extended business trip to Montreal in 1905 where Herman joined the recently founded Montreal ski club. Herman also met with William van Horne to sell construction equipment for the CPR.

Herman and Alice had three children. The family settled first in New York, then Lake Placid and then finally emigrated to Montreal, Canada, in 1928. Herman and Alice became Canadian citizens in 1930. Although he had lived in the United States for 27 years, Herman had never taken American citizenship. He said of his new home “Here in Canada I feel I am more truly at home. Here we have two languages, and the pace is more relaxed. Furthermore, here I can keep my pride in my old country and at the same time be accepted as a true Canadian.”

The family started to ski the Laurentian trails by taking the regular CNR or CPR “ski trains” out of Montreal. This was big business at the time. About 10,000 people were transported out of Montreal every weekend to go skiing in the Laurentians. The Montreal ski club had a cabin at St. Sauveur where the skiers could spend the night. On one such outing with the ski club, the skiers played a game of tag in the dark, and Herman was so fast on his skis that he received the nickname of “Jackrabbit”. This time, the name stuck for the rest of his life.

When the market crash of 1929 came, Herman’s business came to a halt and personal bankruptcy followed. Herman decided to rebrand himself as a “skiing engineer”, and he and Alice rented a small house in Piedmont in the Laurentians. Around this time he did an exploratory ski at Mount Tremblant with some friends. Mount Tremblant was undeveloped and covered in forest at the time, so skiing down it was very challenging. Shortly after, he recommended Mount Tremblant for the first North American Kandahar ski race. This was essentially a bushwhacking race, where competitors had to choose any route they wished, bouncing off trees and rocks on the way down, with the fastest time winning. This event put Mount Tremblant on the map, and it was soon after developed as a ski resort.

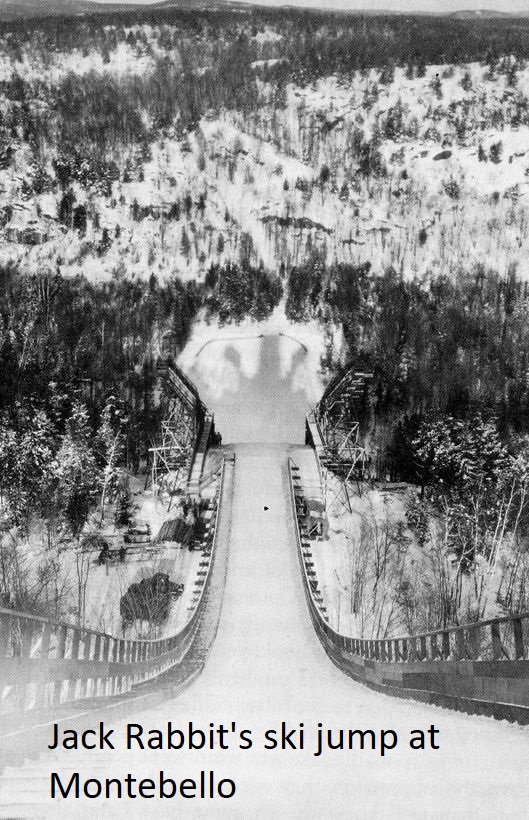

Jackrabbit had established a reputation as a promoter of skiing and started doing consulting work for several resorts including the winter sports facilities for the Seignory club in Montebello. Jackrabbit designed a new ski jump for the facility and it was at the time the tallest ski jump in the world. Jackrabbit also worked on opening up a lot of new ski trails across the Laurentians including the famous 80 mile long Maple Leaf Trail. The CN and CPR rail lines gave him free travel passes because of his work on the trails and because he was such a good ambassador for the sport.

In February 1932 the third winter Olympics were held in Lake Placid, New York. Jackrabbit was selected as co-coach of the Canadian Olympic ski team. Jackrabbit took the team out for a training run up to the top of Mount Marcy, a round trip of 30 miles. None of the team members ever forgot that trip, as it was a challenge to keep up to Jackrabbit who was 56 years old at the time.

Jackrabbit gradually became known all over Canada and the United States, and his name was often used to promote new resorts. He was one of the early consultants brought in to help lay out the ski hills at Blue Mountain in Collingwood. Often when there was a new resort opening up or a special event, Jackrabbit would be summoned and would be flown to the venue, sometimes by private jet. Unfortunately, he was rarely paid for his appearances, so he did not profit very well from all of the publicity. Some of the events were as far away as the Western USA or back in Norway, where he was also well known for his cross-country and ski jumping prowess from his youth.

Jackrabbit liked to inspire others to enjoy the sport of skiing, and he particularly liked to tell the youngsters about his own boyhood experiences to get them enthusiastic about the sport. As a young boy myself in 1963, I met Jackrabbit and spoke with him. I also got to race him that day. At that time, the Toronto Swedish community held a cross-country ski race every year in the hills above Osler Bluff, and one of the participants invited Jackrabbit to come out and join us just for fun. At the start of the race, Jackrabbit – true to his name – took off and left everyone else behind. He easily won that race. I remember thinking this was a pretty impressive feat for an 87 year old. I guess his pep talk must have worked. Like Jackrabbit, I started cross-country skiing at 2½ years old and I am still going strong today.

One year Jackrabbit got a bit homesick for Norway, but didn’t have enough money for a plane ticket home. He went down to Montreal Harbour, and managed to get a job on a Norwegian freighter that was leaving for Oslo. Jackrabbit knew the captain, who was kind enough to give him a job splicing ropes on the crossing. At the time , Jackrabbit was 94 years old.

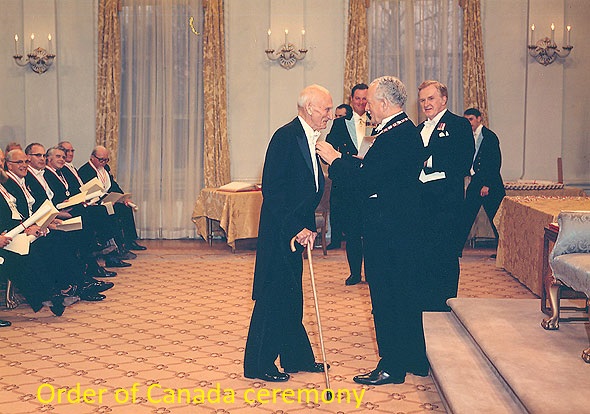

On 22 December 1972, Jackrabbit Johannsen was appointed as a Member of the Order of Canada by Roland Michener for fostering and developing skiing as a recreation activity, and for helping and encouraging generations of skiers in Canada. Jackrabbit said that he enjoyed meeting and talking to Roland Michener as they were both avid skiers.

Jackrabbit continued to be a celebrity at cross-country ski events right up until the 1980s. Here is one tribute to him from skier Gordon Konantz: “In the fall of 1973, I decided to take on the ultimate X/C challenge – The Canadian Ski Marathon held annually each February. This was the biggest X/C ski event in Canada, a timed two-day course 160 km in length starting in Lachute Quebec and ending at Hull, just across the river from Ottawa. The participation was in the thousands. The trail used for the Marathon was originated by Herman Johannsen. ‘The Jackrabbit’ was very much a part of the event. He was in his late nineties at the time and, while he did not participate, he was the honorary patron and opened the event on skis wearing a racing bib. He was also the central figure at the closing banquet on the Sunday following the race. This commanding figure, dressed in a blue blazer, congratulated all the skiers and organizers with great enthusiasm, first in French, followed by English, Norwegian and Cree. All this was said in the space of 5 minutes while he waved his cane over his head and preached moderation in life, in spite of the physical excesses of the past two days.”

The event inspired Gordon so much that when he returned to his native Manitoba, he decided to create a youth program for cross-country skiing in Jackrabbit’s name. In 1976 the Junior Jackrabbit League began in Manitoba as a ski program for boys and girls 6 to 12 years old. By 1981, the program had been taken over by Cross-Country Skiing Canada, and there were over 6,000 Jumping Jackrabbits spread across the country from St. John’s to Vancouver to Inuvik. Jackrabbit was delighted to see the phenomenal growth of the Junior Jackrabbit League. He was confident the future of cross-country ski training for youngsters in Canada was now in good hands. Today, there are still Jackrabbit programs all over Canada including right here in Simcoe County.

Remember those young boys who would go skiing from their little cabin in Nordmarka? In 1983, Jackrabbit was invited to Norway to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the ski club he co-founded in 1883. This was a major event at the little cabin high in the mountains above Oslo. All twenty club members were present as well as the King of Norway. The King was supposed to leave early in the evening but stayed late because he was having such a good time. There was much animated conversation with Jackrabbit and many toasts of aquavit.

Jackrabbit returned to Norway again in 1986 for his 111th birthday. This time he caught the flu, and everyone thought it was over for him, but somehow he rallied. The doctors insisted that Jackrabbit not travel anymore so he stayed in Norway, at an island cottage owned by his son. When Jackrabbit Johannsen passed away on January 5th, 1987 he was the oldest man in the world.

Wee Willi Winkels

Snowboarding has been one of the fastest growing winter sports for the last 35 years. The snowboarding sports first made their debut at the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan. But did you know that there is a major Southern Ontario link to the development of this sport? The individual responsible for this was Wee Willi Winkels. Wilhelm Winkels was the youngest of seven children to immigrate from Germany in 1957. At the time, Willi wasn’t even a year old. His father was also called Wilhelm, hence the name Wee Willi was used for his youngest son.

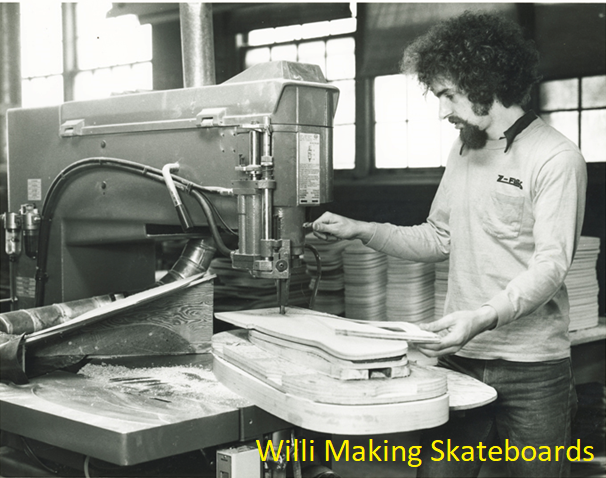

Willi grew up roller skating and skate boarding at the family home in the West end of Toronto. Skateboards at the time were not very sophisticated – clay or steel wheels attached to a solid wooden or plywood deck. As a teenager in the 1960s Willi started to experiment with skateboards. The old wooden boards would often break when Willi tried to do tricks. Willi’s father owned a door manufacturing business. Willi worked with his father to manufacture a much higher quality skateboard. They decided to make the skate boards from a seven ply maple laminate. This construction is still widely used today. Willi also invented the tip tail style of skateboard – an essential feature for all of the trick moves performed on skateboards today. Skateboards also became much easier to control with the addition of urethane wheels.

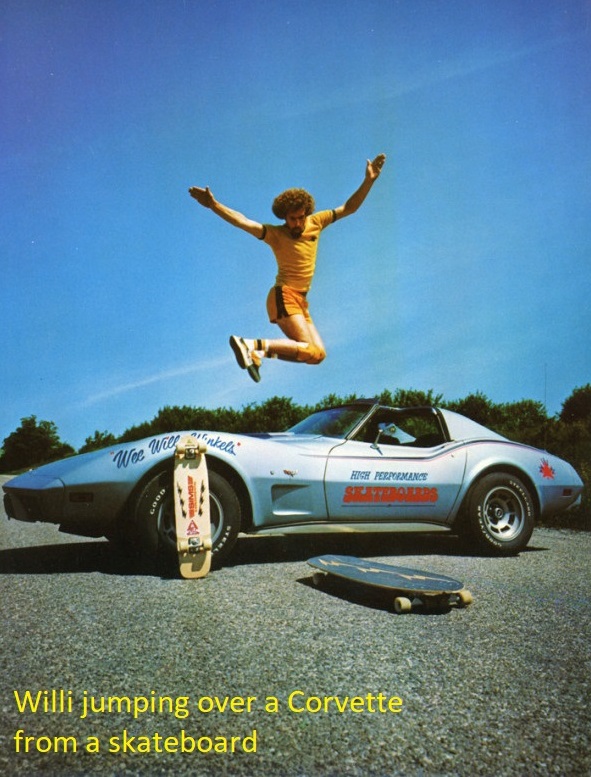

In 1976, Willi made a skateboard for his good friend Lonnie Tofts, who took it down to a skateboard competition in California the next week. It was a revolutionary design, much wider than other skateboards at the time. To make the skateboard more impressive looking, Lonnie had the skateboard silkscreened in a skateboard shop owned by Tom Sims. Lonnie won the skateboard competition doing stuff that no one had seen before. The next day, Tom Sims was overwhelmed with phone calls about the new skateboard, and Tom didn’t know anything about it. Tom found out what had happened and gave Willi a call. It wasn’t long before Willi was making thousands of skateboard decks a week in his dad’s door factory in Brampton and shipping them down to California.

Willi’s family also did a lot of skiing at Blue Mountain in the wintertime. Willi’s father built a chalet at the Apple Bowel at Blue Mountain in 1970. Willi joined the Toronto Ski Club and did some ski racing in the early 1970s. Willi won several races and was also a local champion at Mogul Skiing and Ballet Skiing.

Around 1977 Willi started to date the “girl next door”, or almost next door (actually she lived two doors down from Willi’s family home). Judy was an avid skier and they were married a few years later.

Perhaps it was just a natural progression that Willi would try to combine his love of skiing and his love of skateboarding. Willi’s early snowboards included a bungee cord binding and a grip surface to stop the feet from moving on a wooden skateboard deck. A yellow plastic base helped the board slide on the snow, and the board was first called the “Flying Yellow Banana”. In 1978, he tried out his first snowboard on the slopes of St. Georges Golf Course in the West end of Toronto. Later, he brought the snowboard to Blue Mountain in Collingwood and tried it there.

Willi then brought a pair of snowboards down to Mammoth Mountain in California later that winter. He and Lonnie managed to convince the ski patrol to let them ride the ski lift with the new boards. Tom Sims was with Willi and Lonnie that day but on skis. This was the first time Tom had seen Willi’s snowboard. Tom did a photo-shoot that day. Willi, Tom and Lonnie collaborated to further refine the new boards with steel edges and better bindings before bringing them to market. Willi wanted to call the new invention a “skiboard” but found out this name had already been copyrighted so he decided to call his new invention the snowboard instead. Willi was the first person to coin this new name for the equipment and the sport. The sport of snowboarding took off at Mammoth mountain after that early demonstration. Willi’s wife Judy became the first woman to snowboard on the early “Flying Yellow Banana” , and she was most gracious in allowing me to interview her for this article.

Willi went on to make snowboards for Tom Sims. Tom became a World Champion snowboarder by 1983 and was able to create an empire from the sport. The sport of snowboarding became a very popular winter sport internationally after the 1985 James Bond film “A View to a Kill”. Tom Sims was James Bond’s stunt double for the snowboard scene in that film.

Willi went on to dabble in other boarding sports such as skimboards and wakeboards. Lonnie and Willi brought a wakeboard made by Willi to the summer water ski show in Muskoka in 1985 where it was demonstrated by Lonnie. This was the first wakeboard ever to be ridden in Canada.

Like Jackrabbit Johannsen, Wee Willi Winkels inspired a whole generation of kids with his sports innovations. He built the first mobile wooden skateboard park, complete with a modular half-pipe for a travelling show. He would take his contraption around to towns and cities across the country and demonstrate his skateboards and his many tricks. The kids idolized Willi.

It can be said that Willi was a leading force in the development of snowboards and snowboarding. He introduced the sport of snowboarding to the Town of Blue Mountains where he lived, skied and inspired many kids with the sport. He taught skiing and snowboarding at Blue Mountain for many years. Willi revolutionized the sports of skateboarding, snowboarding and wakeboarding and yet oddly he is mostly unacknowledged as a key innovator and pioneer in all of these sports. If you do a Google search for the inventor of snowboards, Willi’s name isn’t even mentioned.

In one rare acknowledgement, Willi was interviewed by the CBC about snowboarding for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. The number of snowboard events at the Olympics has increased over the years. Today the events include Parallel Slalom, Parallel Giant Slalom, Half Pipe, Slopestyle or Big Air and Snowboard Cross.

Wee Willi Winkels hand in pioneering the sport of snowboarding needs to be recognized. Unfortunately, Willi is no longer with us. He passed away much too young from cancer in March, 2014. However, there have been some measures in recent years to recognize Willi’s contributions to the sport. Blue Mountain Resort has named a ski run after Wee Willi Winkels. The Town of Blue Mountains Museum has created a tribute exhibit to Wee Willi Winkels. There is also a plan to hold a Wee Wlli Winkels day at the Town of Blue Mountains every year on the first Saturday in March. With time, we hope that Wee Willi Winkels will receive his due and be recognized as a true Canadian pioneer in the Olympic snowboarding sports.

History of the Orillia Kiltie Band

Written & researched by Trish Crowe-Grande, History Committee Chair and Cliff Whitfield, Guest ContributorFollowing the success of the Orillia Citizens Band in 1923, winning second place in Class B at the CNE Band Competition, the Kiltie Band brought honour back...

History of the ORILLIA CITIZENS BAND

Written & researched by Trish Crowe-Grande, History Committee Chair and Cliff Whitfield, Guest ContributorIn the late 1800s, it was common to gather at Orillia’s Civic Park (now Couchiching Beach Park) and listen to the Orillia Citizens Band, where hundreds of...

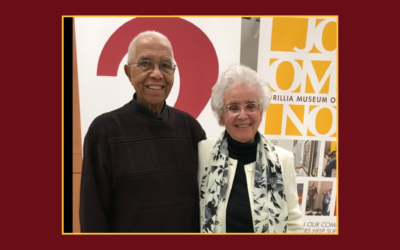

OMAH Celebrates Black History Month – A Tribute to Ron and Ann Harrison

By Mary Ann Grant, OMAH History CommitteeEvery year in February, which is Black History Month, the History Committee at the Orillia Museum of Art & History (OMAH) takes time to acknowledge and celebrate the contributions made by Black Canadians, and to learn about...

Solving the Peter Street Cemetery Mystery

Who owned the Peter Street South cemetery? Your first thoughts might be that this was the St. James’ Church Cemetery, but that cemetery was about two blocks further north on the southeast corner of Peter Street and Coldwater Road. On June 19, 1873, the following...

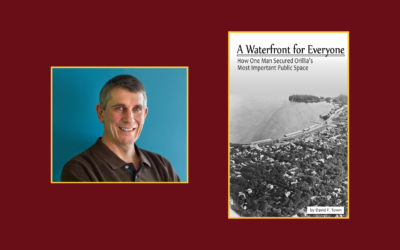

Another Waterfront Transformation

By David Town, Historian, Author of ‘A Waterfront for Everyone’ Orillia Museum of Art & History Guest ContributorWhat a transformation our waterfront is undergoing! There’s a new road going in with better access to the downtown, massive new sewers lie sprawled...

2023 Year-end Message from the OMAH History Committee

As 2023 ends, the OMAH History Committee is very appreciative of the continuous, wide-reaching support for our popular History Speaker Series where local history is celebrated. A full calendar of topics was presented, with our annual kick-off in January featuring Dave...

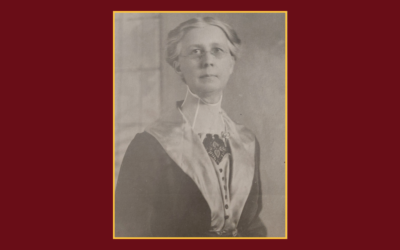

Harriett Todd – Orillia’s Forgotten Hero

By David Town, Historian and Guest ContributorHarriett Todd, image provided by David TownFew people have had a greater influence on Orillia than Harriett Todd. Most of us only recognize her name because a school has been named after her in Orillia, but 100 years ago...

Great Grandparents Immigration to Canada

By Janet Houston, OMAH History CommitteeAlfred and Jane HuckerWhat could tempt a middle-aged couple to emigrate from England to a distant part of the Empire in 1912? Fifty years of age is not now considered old as it was thought then. Nonetheless, this adventurous...

The Hallen Family’s Arrival in Orillia

By Fred Blair, OMAH Family researcher and guest contributerEleanora’s Diary, November 4, 1833 “In the morning, before we went out of the steam vessel, George put his fish [line] in as he saw a good number of fish. He caught nine very soon, but he had not time to...

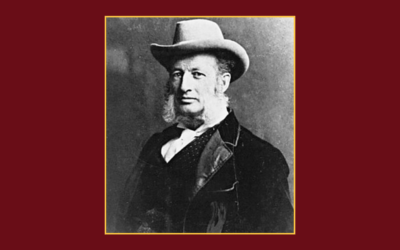

All About the O’Brien Family, Founders of Shanty Bay

By Trish Crowe-Grande, OMAH History Committee ChairLucius Richard O’Brien portrait undated M.O. Hammond Collection: National Gallery of Canada ArchivesEdward and Mary O’Brien At the age of fourteen, Edward George O’Brien entered the naval service as a mid-shipman, but...