By David Town

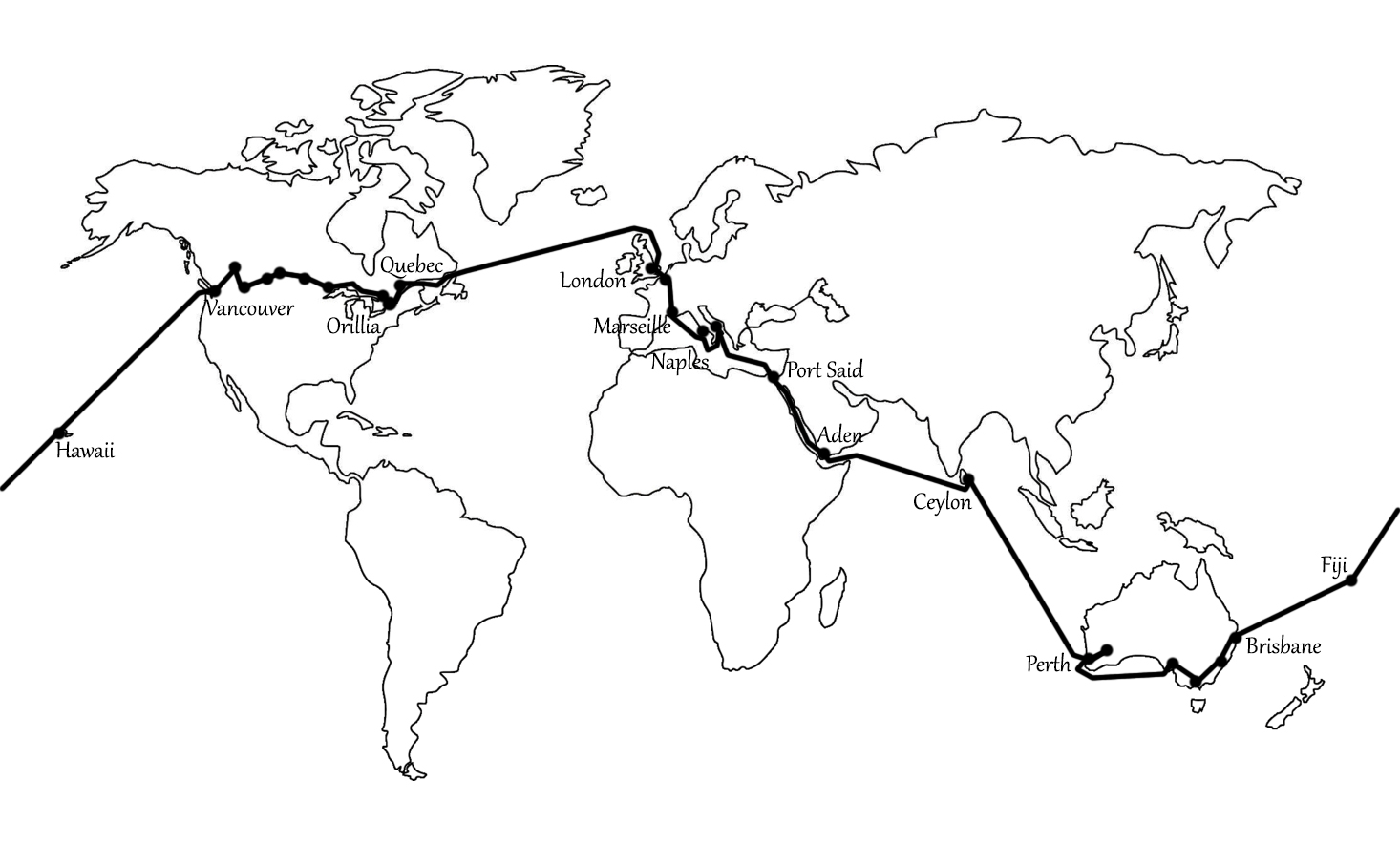

It was another proud first for Orillia, and an astounding accomplishment – but as John Miller stepped off the train at the Orillia platform the only people there to greet him were his family. He had single-handedly negotiated, organized, and managed the first around-the-world tour by any team in any sport from anywhere in the world. And this was in 1907, when few people travelled more than 20 miles from home in their lifetimes. On top of that, none of the players had to pay a cent for the five-month trip, and there was a small surplus of funds left over to put in the Orillia Terriers coffers. It was an amazing accomplishment, but already long forgotten, just six weeks after the last game had been played.

Lacrosse, Canada’s “National Game”, was struggling in Australia, unable to attract even a fraction of the crowds that cricket and football could. In search of a spectacle to boost interest the Aussies had spent almost ten years trying to entice a Canadian team to come “down under” to play a series of demonstration games. The cost had intimidated every other team.

But John Miller, manager of Orillia’s Terriers senior team, a perennial powerhouse in Canada, saw the possibilities. He convinced the Australians that the Canadian team would fill the stands and the gate receipts would pay for their travel across the country, and that took some convincing. Then he assured his team that a series of games across Canada on the way to the ship in Vancouver would pay for that end of the trip. He convinced them both to take the risk and the matches were set.

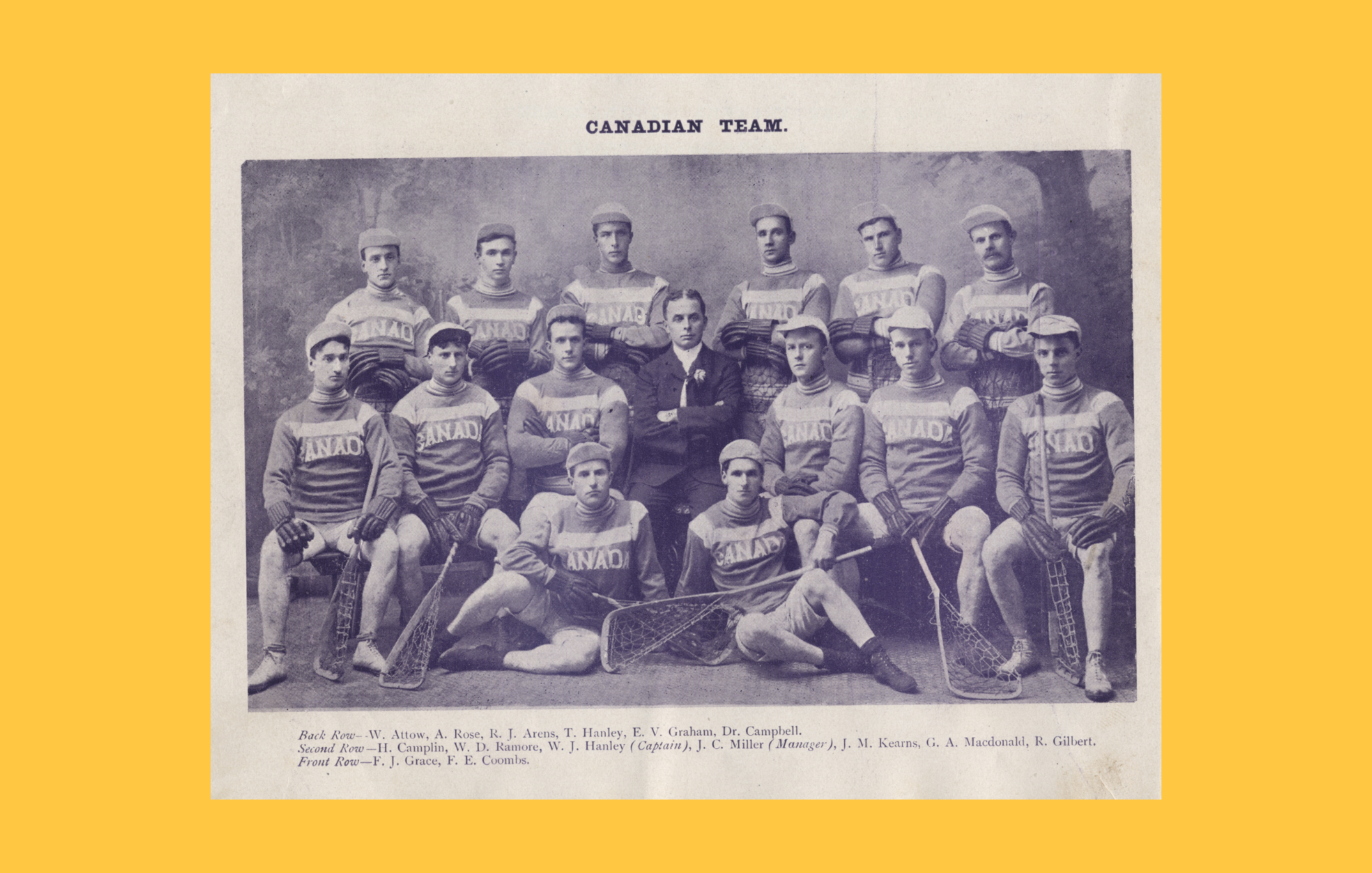

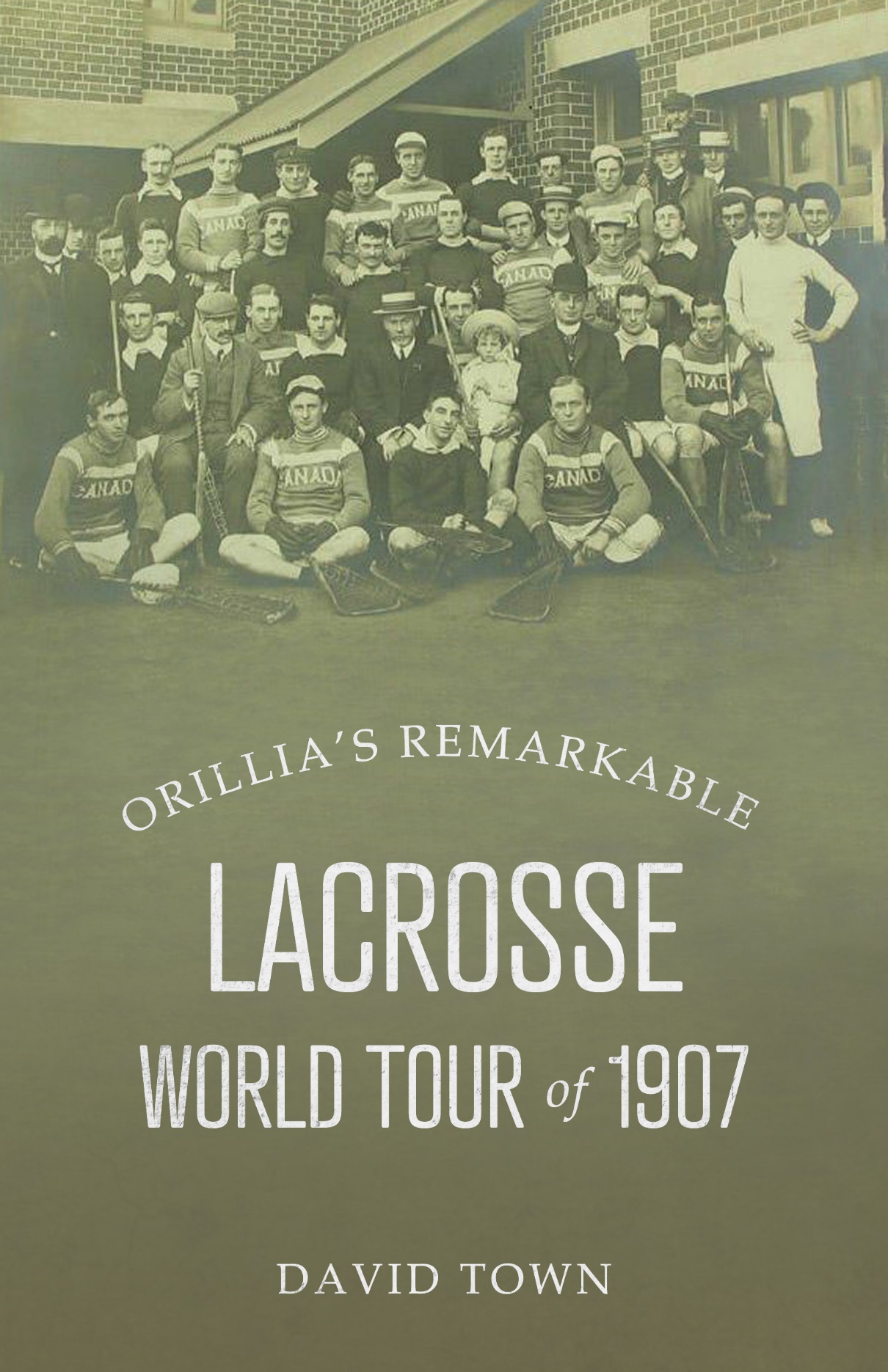

In Australia lacrosse was a “gentleman’s sport” like cricket here today. In Canada it was violent and brutal. The Aussies’ only request, afraid of Canada’s reputation, was that Miller not bring any “boozers” along on his team. So, with a core of eight Orillia Terriers, he recruited another seven all-stars from across Ontario, all university men, and non-drinkers.

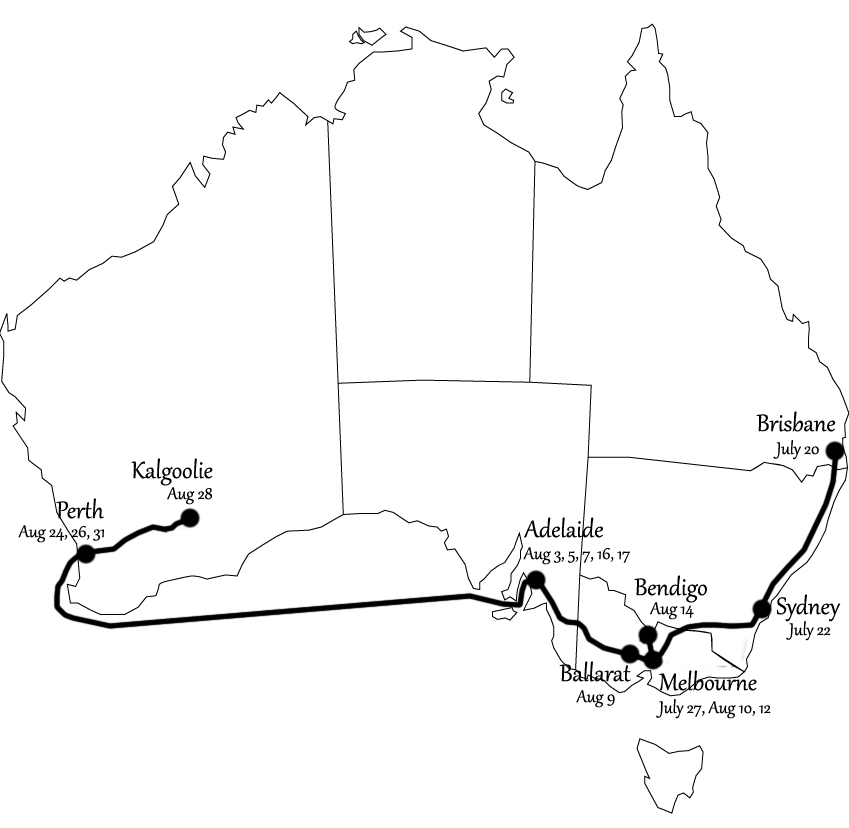

After nine games against the best teams across Canada (and a 7-2 record), they headed off to Brisbane, a 21-day steamship trip. And the first game there, July 20th, was eye-opening. No one had thought to discuss the rules and both teams were surprised to find out how different each played the game. The Aussies used a field twice the size and a ball half the weight. They had no rough stickwork allowed and different penalties. Though the Orillians won handily, negotiations started immediately over what rules to use, and that continued the entire trip.

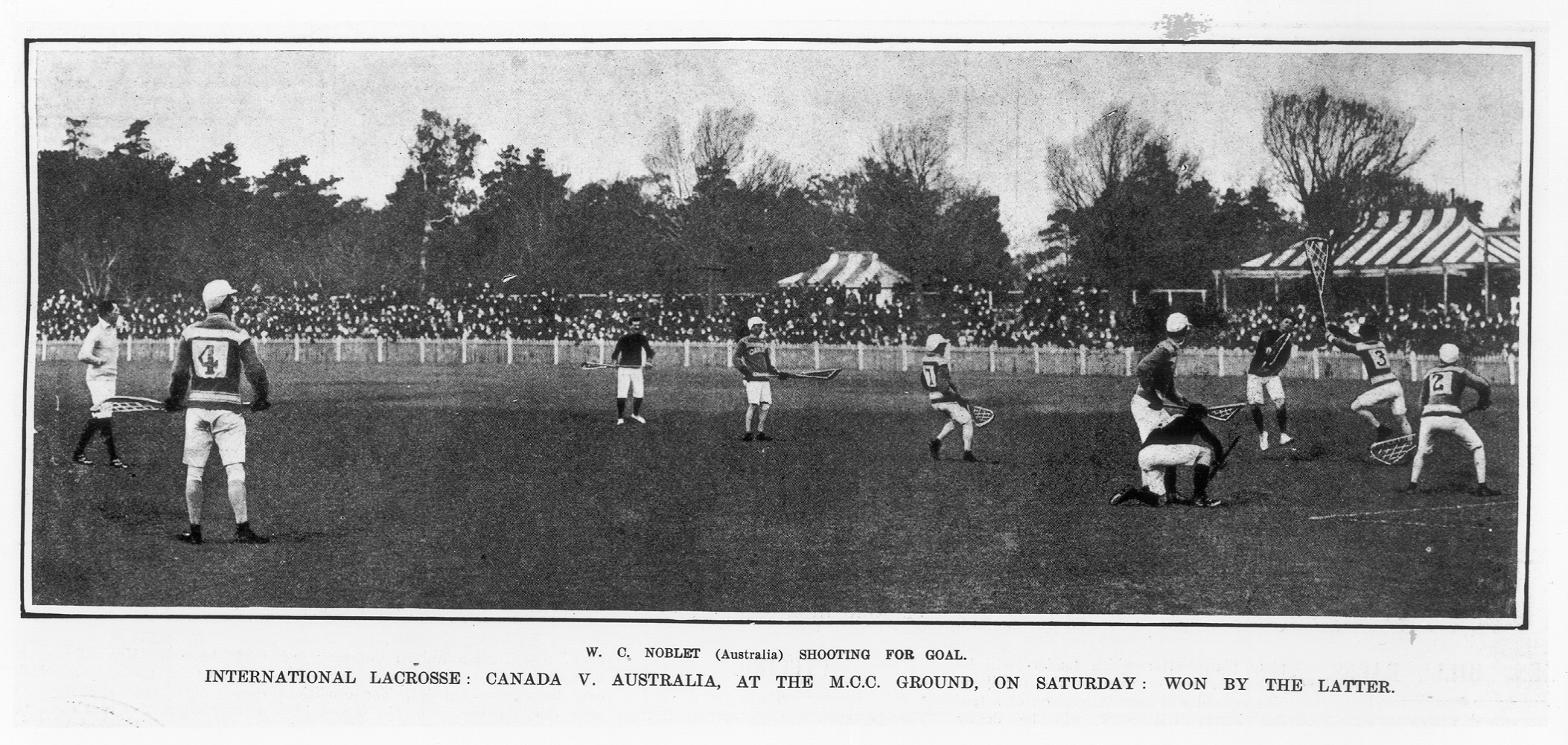

They played 16 games in nine different cities, winning all the games against local all-star teams comfortably. But the four games against an Australian All-star team got quite interesting, to say the least. The first of these was just their third game in Australia, and the rules were stacked against Canada with the huge field, light ball, and endless penalties against Canada for routine plays acceptable back home. The Aussies won that game 5-3, stunning the Canadians.

In Canada lacrosse was a team game of rapid, deceptive, short passes among a phalanx of players slowing advancing downfield, looking to work in close for quick, short shots. The Aussies used long passes and streaking solo rushes down the sidelines and then long bad-angle shots on net. There was no “rough stuff” in their game. Caught totally by surprise, three of the Australian goals went in because the Canadian goalie and defencemen never suspected a shot was going to come from such a lousy spot.

After that it got serious. They weren’t “demonstration games” any more. National pride was on the line. Miller became aggressive in his negotiations over the rules and a hybrid of the Canadian and Australian rulebook was gradually adopted.

The second game against the National Team six days later was a 6-3 win for Canada. Then, after a 4-0 whitewash of the National Team in a less serious exhibition game spontaneously added to the schedule (to milk the cash cow crowds the games were drawing, just as Miller had predicted), the stage was set for the final rubber match for bragging rights on August 17th in Adelaide.

But before that game the Aussies scheduled the Canadians to play eight games in 11 days in five different cities incurring train travel of 1,600 kilometers. An exhausting schedule designed to maximize gate receipts and not to just tire out the Canadians, they were assured. The Canadians walked onto the field for the big game oppressed by a baking hot 34°C field and having played just the day before. They were tired.

Intent on winning, what ensued was “the roughest play Australia had ever seen”. Holding, body-checking, tripping and all kinds of “stick work” drove the Australians into conniptions. This was not a gentleman’s game. But it was a demonstration of “the Canadian game”, as was originally requested.

The Aussies tried to retaliate, to give as good as they got, but were hopelessly outmatched in the violence department. At the end of the first quarter Canada was up 5-1 after some spectacular passing plays. The Canadians were rough, but boy, could they pass the ball – look-the-other-way passes, behind the back passes, passes so fast the defence lost track of the ball. The game looked in the bag for Canada.

But in the third quarter, down 6-1, the Australians came on, playing “the best lacrosse ever seen in Australia”. They potted three unanswered goals to make it 6-4. The Canadians were done in. The heat, the big field and that exhausting stretch of games all caught up with them as the Aussies began to run right past the defenders. Canada played for time, ragging the ball, literally walking up the field on the attack.

Then it happened. The Canadian Camplin, in checking the Australian attacker Humphris, “smashed him” with his stick. Another Australian came to Humphris’ rescue and laid into Camplin “vigorously with his fists”. Suddenly all hell broke loose as all of the Canadians, so familiar with bench-clearing brawls, lit into the nearest Australian as they converged on the fracas. The Australians had never seen this before. The huge crowd erupted in an uproar, shocked at the poor sportsmanship. The referees were stunned into helplessness, rooted in place. The donnybrook continued for some minutes before the police finally rushed onto the field to restore order. They came out on horseback, pushing the brawlers apart, others wrestling the players apart. It was an appalling display.

But there was five minutes left to play and Australia had been dominating the game, down just two goals. The referees let the game continue after the two original combatants were sent off.

Resorting to another Canadian tactic, the Terriers took the ball behind their own net and began playing catch, tossing it side to side across the field far out of the Australians’ reach. It was a miserable way for such an intense and interesting game to end. No one even pretended to move towards the Aussie goal. But Canada won the rubber match 6-4 to take the series and save their honour. The demonized Canadians were on their ship to Perth less than an hour after the game ended, high-tailing it out of town.

After a few more unremarkable games in west Australia the team boarded ship to steam back to Europe for a three-week holiday, then back to Canada. The out-of-town players dispersed, heading to their home towns, and most of the Orillians headed to the University of Toronto, three weeks late for classes. Only manager John Miller took the train home to Orillia.

They had travelled 9,000 kilometers by rail and 30,000 kilometers by ship over five months, played 25 lacrosse games (with a 22-3 record), and it cost them nothing. The gate receipts covered all the costs. John Miller deserved a better welcome home.

Click HERE to purchase Dave’s book, “Orillia’s Remarkable Lacrosse World Tour of 1907” from the OMAH Shop and read the complete story of this remarkable team.